Before today’s corporate-sponsored arena concerts and big-money endorsement deals, there was a time in hip-hop when its stars were not far from the people and places that gave rise to the culture. LL Cool J could go to a high school in East Harlem and perform to an adoring crowd, or DMC could hang out in Hollis, Queens, and chill out by an ice cream truck.

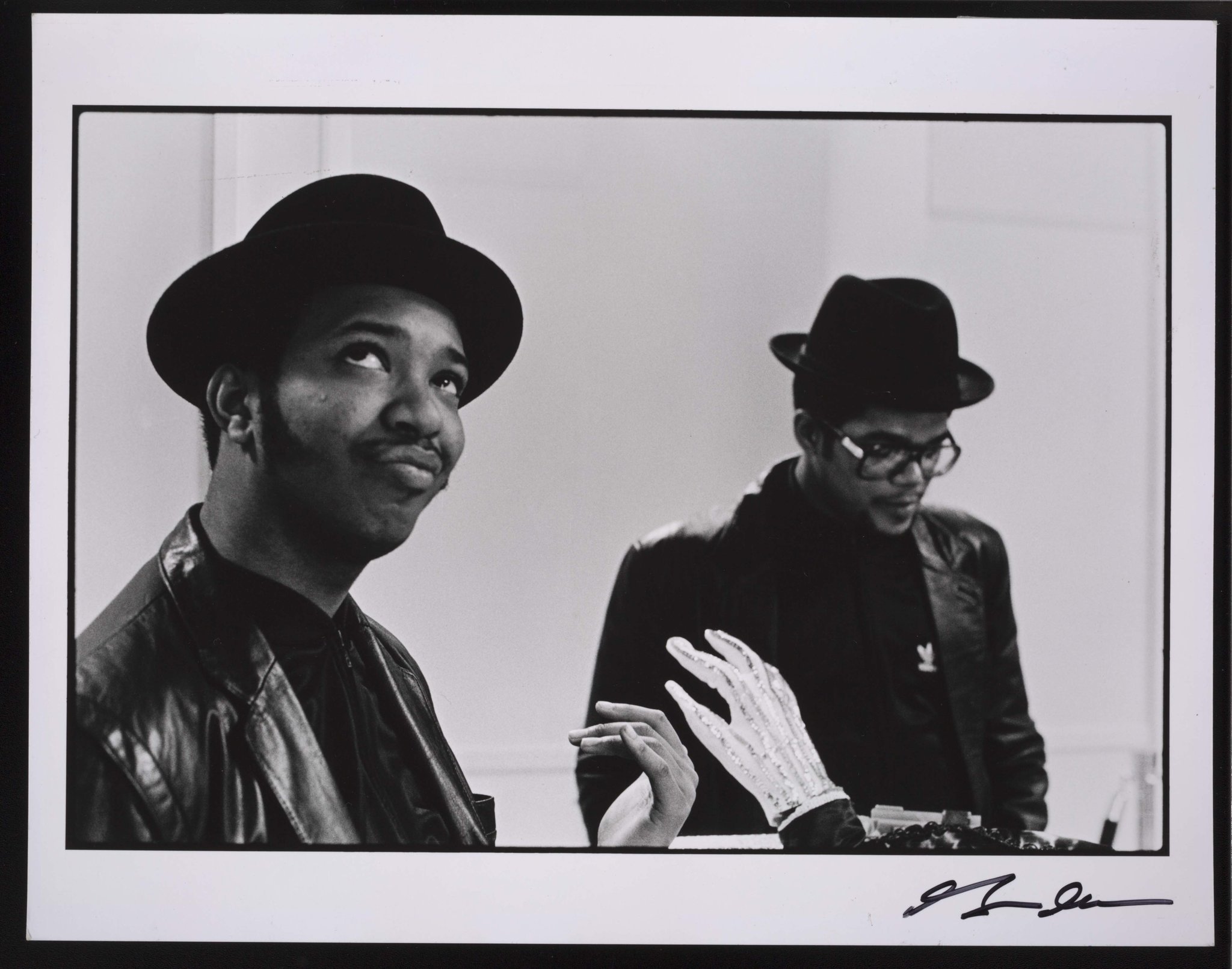

Those days seem as distant as the time when shell-top Adidas and shearling coats were in style. But images from that era form the core of a new collection acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Obtained from Bill Adler, the writer and former music industry publicist, they offer a survey of hip-hop’s golden era, reflecting its energy, style and fun (although it also includes some images taken in the 2000s).

Among those represented are many pioneering female rappers like Sha-Rock, Queen Latifah and Roxanne Shanté, revered elders like Rakim and Afrika Bambaataa and cut-ups like Biz Markie and Flavor Flav. Some of these images will be on display when the much-anticipated museum opens in the fall.

“The culture has morphed and changed as things do over time, but these pictures speak to the grass roots nature of it,” said Rhea L. Combs, the museum’s curator of film and photography. “That is the special quality of this collection. It touches on all of those important moments that are kind of nostalgic: You had jams, you had concerts, you had street ciphers. It included not just the M.C., but the D.J., the dancers and graffiti artists. This collection epitomized a nice constellation of these important moments of a very real and American moment in history.”

Mr. Adler’s interest in these images — which were collected during his time running Eyejammie Fine Arts, a hip-hop photo gallery in Chelsea in the early 2000s — reflects a longstanding interest in documenting the music that interested him. In college, where he was a young music critic for the Ann Arbor Sun, he began tracking down photos and other information about the acts he would be reviewing. At record stores, he realized, there were publicity photos, posters and other items that too often wound up in the trash. He soon began to scoop them up.

He already had material on some hip-hop artists by 1984, when he went to work for Russell Simmons as director of publicity at Def Jam records. In that job, he was able to commission photographers to make images of the label’s acts.

“I also had my historian’s hat on,” Mr. Adler said. “I would keep a copy of everything we produced. I had been doing some of that before, but I started doing it intensely while working for Russell.”

The images in the collection are done by a range of photographers, including Janette Beckman, David Corio, Ricky Powell, Michael Benabib and Harry Allen. From studio portraits to candids back in the neighborhood, some of them portray a certain ease, intimacy and trust. In some you see artists like Queen Latifah as they first took the scene; KRS-One with his then-wife Ms. Melodie; the Beastie Boys goofing around or Run-DMC posing with the Eiffel Tower in the background.

Some images still have the power to surprise, like a shot of Big Daddy Kane getting his hair shaped up before going onstage (Slide 2).

“I love that one,” Mr. Adler said. “It seemed like the kind of photo you’d see in Life magazine a generation ago, so everyday but also exalted in a way.”

That everyday nature spoke powerfully to Ms. Combs, who grew up in Detroit listening to the music of many of the artists in the collection.

“This was my generation’s Motown,” she said. “It’s who I am. When I think about my youth, I think about getting dressed listening to ‘Bonita Applebum,’ reading Vibe magazine cover to cover. It’s part of my identity. It’s a language that helped shape my language and the lens through with I understand the world.”

That lens was just as much influenced by Russell Simmons, who Mr. Adler said had a keen understanding of the music and its roots. He said that while Motown had its singers take pointers on how to dress and talk as a way to appeal to mainstream audiences, Mr. Simmons insisted that hip-hop culture did not need to be toned down.

“He made it clear to me that it’s not just rap music, but a whole culture from a super-creative community,” Mr. Adler said. “A generation after Motown, Russell thought we didn’t have to water down that culture in order to cross over. In fact, we’re going to do what we do at full strength and pull the mainstream in our direction. We didn’t cross over to them. They crossed over to us.”

lens.blogs.nytimes.com